I’ve come a far way with my training. I don’t usually get many first anymore because I’m working on perfecting my flying skills, and not learning anything new. However I just finished a flight with a new first; night flight. Night flight is mandatory for students to obtain, and in order to get their private pilot license, we need at least 5 hours of it. I just got 1.9 hours of night time so far.

Night flight is typically conducted the same as day flying. The major difference is that more emphasis should be made at looking at the flight controls while in the air. Just like flying in the clouds, or under foggles, night flight doesn’t offer many ground references. There isn’t a horizon, and on moonless nights, it could appear like you’re flying in a black hole. It’s important to understand the illusions associated with night flight, and also IMC conditions.

I got to the airport around 5:30pm local time. I did the normal preflight briefing; paperwork, weather, and weight and balance. After I got the keys for N157LH, I walked across the ramp to preflight the airplane. As I unlocked the door, the sun was just going behind a hanger. In order to get credited with night time, you need to be flying after 30 minutes past the sunset time. So with the sun setting at 6:00 pm, I needed to wait until at least 6:30 to takeoff. If I took off at 6:25, than those 5 minutes wouldn’t count as night time. As I preflighted the plane, the sun sank lower and lower until it was completely set. By 6:20 my instructor and I were in the cockpit. It takes more than ten minutes to start the plane, taxi to the runway and go through all the checklists so we weren’t worried about waiting the 30 minutes.

Taxiing

The biggest thing I noticed about taxiing at night is that even though there are the blue taxi-way edge lights, it’s still difficult to see where an intersection is. Unless looking right down the taxi-way, adjacent lights, for an adjacent taxiway look out of place. Other than that, it’s the same as taxiing during the day. After I got to the runway hold position, I set the panel lights for minimum brightness and got everything ready for my flight; lights on, flashlight ready, maps unfolded. I radioed to the tower and received the takeoff clearance. As I taxied onto the runway, I looked down the runway. The sight of looking down a 6000 foot runway with the edge lights on is remarkable. It looked like the lights went to infinity.

A similar scene to what I saw

|

Looking down a runway

|

Blue taxiway lights

|

Flight

As I climbed out of the field, I couldn’t help looking out the window. The sight was exactly what pictures and movies make night flying look like. There were intersections of roadway lit up, bodies of water without lighting, and I was able to see the entire outline of Long Island by the time I was at 2000 feet. I monitored the instruments carefully and kept enjoying the view. As I made my way out to the practice grounds, my instructor and I went over the illusions. Coriolis, elevator, somotogravic, and all the others. Once in the practice area, I practiced steep turns. I got the plane configured for the maneuver and went over the procedure to execute a steep turn in my head. 45° bank, maintain 3000 feet and keep my airspeed at 90 knots. I rolled into a left steep turn. I forgot that I was flying at night but realized once I started the maneuver. Without the horizon, it’s hard to tell if the nose is pointed down or up. I kept fluctuation between 2900 feet and 3100 feet. As I rolled out, and leveled the wings, I checked the instruments; not bad for my first time, and at night. After practicing a steep turn to the left, I practiced stall recoveries. I did well on these, mainly because it’s almost the same as doing them under the hood. It’s even a little easier since I have a few ground reference points.

As I was flying I realized that while it’s the most important thing, altitude depiction is very tricky at night. While I was at 3000 feet, it seemed like I was at only 1000 feet. And as I descended to 1500 feet, my perception of height above the ocean wasn’t any different. Also, lights can be tricky. At one point I thought that a string of lights was the horizon. However, my instructor corrected me. The lights I saw were actually a line of airplanes inbound to land at Kennedy Airport. There were always at least 10 lights in line, stretching over 100 miles (my instructor said. I couldn’t tell the distance). Finally, after getting a little more use to flying at night, we headed back to Republic for landings.

Landings

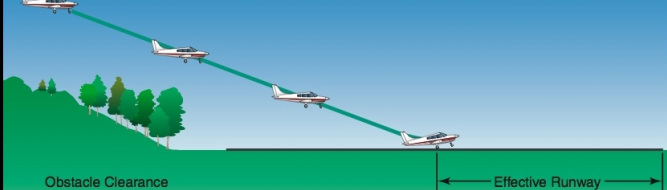

Like everything else, night landings are the same at night as during the day. However, the perception of the runway changes drastically. The first landing I did, my instructor had to put power in himself because I would have crashed well before the runway threshold. After 2 or 3 attempts, I got the hang of it. The trick to night landings, or at least my philosophy, is to come in high. This allows you to point the nose down at the runway. Doing this allows the lights to shine on the runway. Seeing the runway is obviously better than not seeing it, so the landing can be made more efficiently.

After 1.9 hours, we taxied back to Farmingdale’s ramp and locked the plane up. My instructor was happy with my first night flight, so I was as well. My next night flight isn’t for another month or so, but next is cross country work.

Today was a great lesson. I made good progress with my short and soft landings and takeoffs.

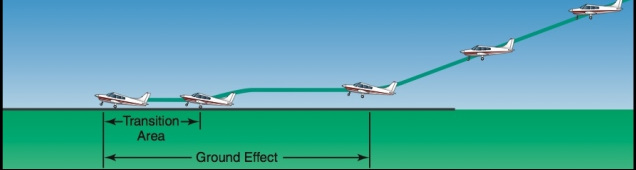

Soft Field Takeoff

I started the lesson with a soft field takeoff. The goal of this maneuver is to takeoff safely and efficiently from a soft field, such as dirt or grass. I did all my pre-takeoff checklists and lined up on the Alpha side of runway 32. Once I got clearance for takeoff, I put in 25 ° of flaps and lined the plane up with the centerline. Without stopping, I added full power and brought the controls fully aft, or back. What this does is it allows the nose wheel to come off the runway as soon as possible. The longer it’s on the runway, the less efficient the wheel is (due to small bumps in the grass). Today I was practicing on Republic’s asphalt runway, but it was a simulated soft field. Within 2 seconds of the nose wheel lifting off the runway, I felt the main gear wheels lift as well. Once all wheels were off the ground I lowered the nose so I could stay in ground effect. The purpose of this is to allow the airplane to gain sufficient speed for a climb. With the controls fully aft, the plane rotates at a slower speed. My first maneuver of the day was successful. I climbed out at 79 knots and made left traffic for a landing

Soft Field Landing

The first landing I tried was a soft field. The goal of this maneuver is so set the wheels down as softly as possible, so they don’t dig into the dirt or grass. In order to do this, I did a normal approach to landing until I was about 20 feet off the runway. Once there, I brought the power back to idle so I could do my round out. In the round out, I added the extra power, which allowed me to float in the ground effect. This allowed the plane to touch down softly. As I allowed the wheels to touch down, I held the controls aft. If the nose wheel strikes the ground too hard, it could make a divot in the grass and flip the plane over. To prevent this, you keep the controls aft so the nose wheel stays off the ground until the plane is going as slow as possible. Once all wheels were on the ground I took the flaps out and performed the touch and go for another landing.

Short Field Landing

After a few more soft field landings, I started practicing short field landings. Luckily at Republic Airport, the runways are both over 5000 feet long. I’ve never needed more than 1100 feet for a landing or takeoff since I started my training; however, not every runway is 5000 feet. To practice a short field takeoff, we simulate that the runway is much shorter. I picked out my spot on the runway, the first centerline stripe, and aimed for that. In order to stop in the quickest distance, the approach speed is 5 knots slower than usual. Normally, my approach would be at 65 knots, but for the short landings, I came in at 60 knots. As I got over the chevrons at the beginning of the runway I took out all power. As the plane came over the runway threshold, I tried to keep the wheels off the runway for as long as I could. I put the plane down at the end of the first stripe; about 120 farther than I wanted. Fortunately the practical test standards are 200 feet so I was well within limits.

Because we didn’t do any taxi-back takeoffs (land, taxi off the runway and then taxi back to the runway) I couldn’t practice the short field takeoffs. I’ve tried these many times in the past so I ‘m pretty comfortable with them anyway.

Today I prepared for my first cross country flight. Before students start going on cross country training flights, they first must understand what they’re doing. It would be pointless flying to a different airport if the student didn’t know how they got there or what the procedures were for cross country flight. Today, my instructor showed me what I need to do prior to the flight, in order to get ready for a cross country flight lesson

Pilotage and Dead Recogning

First off, there are many ways which pilots navigate the skies. A common, well know method is by GPS. GPS has become standard in all new built aircraft. However, plane which were built in the 1960s are still being flown all over the country today. While some pilots spend money to have GPS systems installed on older aircraft, most planes from decades ago must rely on other means of navigation. During VFR flight, the standard way to navigate is by pilotage and dead recogning. Pilotage is the process of navigating by visual references on the ground. For example, a pilot flies until he sees a point which can be seen on his map. This can be a building, a road, bridge, or anything distinguishable. Once the pilot locates the object on his chart, he knows where he is. Then, he’ll fly in the direction of another known marker and continue to do so until he reaches his destination. Dead recogning is the process of adding math to pilotage. By knowing speed, altitude, winds, and distances, pilots can know when they will be over a known location at the precise moment they reach it. Dead recogning is how private pilots are trained at Farmingdale Aerospace, along with student pilots all over the country.

Navigation Log

All time, distance, fuel, altitude and other pertinent information is recorded on a navigation log. The first thing on the log is an area where the pilot can write down waypoints. This can be anything from an airport or VOR to a bridge, intersection of roads, or buildings. Almost anything can be used as a waypoint, as long as it’s clearly visible from the desired altitude and if it sticks out from its’ surroundings. The goal is to get from one airport to another as directly as possible. It’s advantageous to pick waypoints which make the most direct line possible between the two airports. Of course, the majority of the time, the flight won’t be straight and will “zig zag” a bit.

During my lesson today, I filled out a mock navigation log, which would have taken me from Republic Airport to Dutches County Airport in Poughkeepsie, NY. Including the starting and ending airports, I had 7 total waypoints. Once I decided on suitable waypoints, I measured the distance in, NM, from waypoint to waypoint. Because winds play a vital role on timing and correction angles, you need to compensate for wind when determining the true course from one waypoint to the other. It’s also important to note that when planning for winds, pilots must use the winds aloft data, and not surface winds. Once winds correction angles had been established, I then compensated for variation. Variation is the angular difference between geographical North Pole and the magnetic north pole. In my area of New York, the variation is about 14°W; so I add 14 to my true course (east is least, west is best). Next was magnetic heading. This is the final heading

| |

which the nose of the plane should be pointed in order to arrive at the desired waypoint. In order to get this, I had to add or subtract deviation. Deviation is the error in the heading indicator due to the magnetic and electrical fields inside the plane (often caused by the instruments, GPS, cell phones etc.). Normally, there isn’t more than 1 or 2 degree deviation for each radial. Any wind, time, fuel and distance can be calculated by using a “Whiz Wheel.” A Whiz Wheel (above) is a flight computer; one side has a tool which allows for wind angle correct, while the other side has two turnable wheels for computations.

Once the magnetic heading was established, I needed to find out fuel consumption. In order to do this, I needed to know how much fuel the airplane would burn. Luckily, that information’s provided in the aircraft’s POH. Because I know what my speed will be, and the distances between waypoints, I can calculate exactly what time I should be at each way point. Also, because I know the distance and the fuel consumption rate, I can calculate the amount, in either pounds or gallons of fuel the trip will need.

The last section on the navigation log is for additional information. There are spots to write down both the departure and the destination airports’ frequencies; tower, ground, ATIS, FSS, and any other frequencies, which are important.

Once completed, the pilot then needs to call the appropriate flight service station to open the flight plan. This means that the pilot puts his trip on record. Once airborne, or just prior to takeoff, the pilot will open the flight plan so the flight service station knows the plan is active. Once the trip has been completed and the destination airport is reached, the pilot must close the flight plan. If not closed, the FSS will issue a search and rescue operation after 15 minutes of expected time of arrival at the destination airport. Because today was practice, I didn’t open the flight plan. However, it was good practice for my first cross country flight next week.

The past couple of days, here in the New York metropolitan area, have seen cloudy skies, rain, and overall poor weather. The majority of the time, IFR rules have been in effect. There are two types of flights, and flight plans, which pilots can file; Visual Flight Rules and Instrument Flight rules. It’s important to know the difference between the two. In order for your better understanding, this post will describe what each is and the importance of both.

Stable Vs. Unstable air

First off, most people associate clear skies, warm weather, and clean air as good weather for flying. This isn’t entirely true. While clear skies are positive to flying, they usually indicate unstable air. Unstable air is described as air with the tendency to rise vertically; which can be associated with cumulus clouds, good visibility, showery precipitation and turbulence. Therefore when one looks up and sees bright blue skies, it usually means planes in the air are experiences some degree of turbulence. On the other hand, stable air is much more conducive to peaceful flight. However, in order for air to be stable, air must be the opposite of that which describes unstable air. Stable air does not rise vertically and is associated with stratiform (or layered looking) clouds, poor visibility, steady precipitation, and no turbulence. When you go outside on a day where it’s overcast and has been raining constantly for an extended period of time, the planes in the air feel little turbulence. Unfortunately, they are flying in the clouds and can’t see anything.

Visual Flight Rules

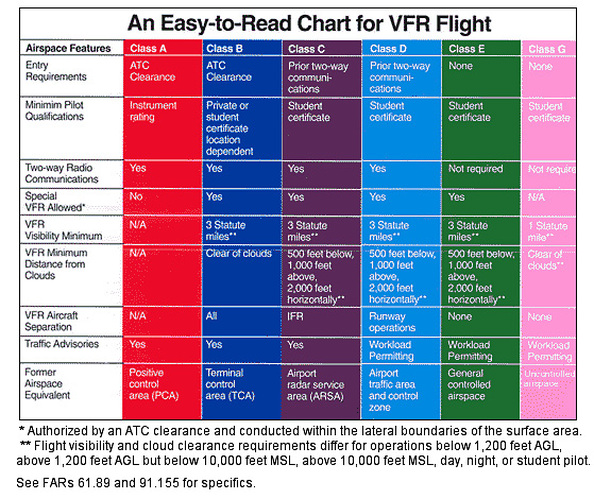

This brings the discussion to VFR vs. IFR flight. In order to fly VFR, pilots must “play” by certain rules. The FAA defines visual flight rules as “The pilot must be able to operate the aircraft with visual reference to the ground, and by visually avoiding obstructions and other aircraft.” Basically, they rely on sight to fly the plane. The weather minimums, described in the FARs sec. 91.155 state: (a) Except as provided in paragraph (b) of this section and §91.157, no person may operate an aircraft under VFR when the flight visibility is less, or at a distance from clouds that is less, than that prescribed for the corresponding altitude and class of airspace in the following table. The chart to the left (click to enlarge) describes what each airspace’s limitations are for VFR. Because each airspace has its’ own level of air traffic, VFR rules are different for each. If, while flying in the appropriate airspace, a pilot cannot maintain these weather minimums, than he or she will have to file an IFR flight plan, or change course or altitude to stay in VFR flight.

Instrument Flight Rules

If weather falls below these minimums, than a pilot must file an IFR flight plan, prior to departure. The FAA defines IFR flight as “Rules and regulations established by the FAA to govern flight under conditions in which flight by outside visual reference is not safe. IFR flight depends upon flying by reference to instruments in the flight deck, and navigation is accomplished by reference to electronic signals.” This means that if conditions exist below the weather minimums, IFR flights must be flown by reference to the flight instruments, and by electronic signals from the ground, or controlling agencies; tower or ARTCC. The FARs state in sec. 91.167 what the requirements for IFR flights are.

Pilots who have not yet received an instrument rating are not permitted to fly IFR. In order to do so, the student pilot must first obtain a private pilot license, then enroll and earn an instrument rating. This course teaches student pilots the operations of instrument flying.

The picture to the left (click to enlarge) shows the former control tower at my base airport, Republic – KFRG. (A new tower on the other side of the field controls all flight activity; however, this tower was used decades ago.) Every towered airport has a rotating beacon, and Republic’s is atop the old tower. The beacon rotates at night, and also during IFR conditions. Also, the rotating beacon identifies which type of airport it’s on. If a beacon flashes a white light, followed by a green light, (you can see in the picture the green light is flashing by) the airport is a land, civil airport. If there is a while signal followed by two green flashes, the airport is a land military airport. When the beacon flashes a white, then yellow light, it’s a sea port; and if the beacon flashes white, green then yellow, the beacon’s located on a helipad.

Knowing the difference between VFR and IFR is important for pilots. Pilots who don’t follow the proper rules are subjected to license revocation, fine, or another form of punishment by the Federal Aviation Administration

So this “winter storm” has grounded most students from flying today, even without any snow. VFR flight, or visual flight rules, dictates whether or not certain students can fly. It all depends on the training. For a student like me, I cannot fly on a day like this. Unless the ceiling (lowest layer of broken or overcast clouds) is above 3000 feet and visibility is 5 SM or more, I’m grounded. However, when I become an instrument student (learning to fly in clouds, and bad weather) I can go out in a day like this.

While flying VFR, pilots must follow rules on ceiling, and visibility, as well as how far away they are to stay from the clouds. Each airspace has its own rules. The chart below does a good job to illustrate the visual flight rules in the different types of airspace.

Skies clear. Wind at 6 knots from 320°. Altimeter at 29.95”. Temperature is 14°C/ 58°F. Pretty much a perfect day to fly. I got to the flight center 30 minutes early to give myself enough time to get the weather, ATIS, figure out landing and takeoff distance, and determine the weight and balance for the airplane. Today’s lesson was going to be a fun one. We would start by taking off runway 32, and travel north to the north practice grounds. After doing a few stall recoveries, I was going to go up to Bridgeport Airport to practice touch and goes there. I had never been to Bridgeport and was excited to visit a new place. After all, that’s what flying is all about, traveling. However, I never made it to Bridgeport. I didn’t make it to the practice field. I didn’t even make it off the ground.

After I got all the information I went out to the plane to inspect the plane and make sure everything was good. As I went through the checklists, I made sure every item was correct, as I usually do. First the cockpit checklist, then the right wing followed by the forward fuselage. Next was the left wing and finally rear fuselage. After all that I did a complete 360° walk around and was confident the plane was all set. I went back into the cockpit and got ready for the flight. As I waited for my instructor to come out, I opened the aviation map to the places I would be at, and got the frequencies I would need for the new airport I was going to.

My instructor finally came out checked the airplane himself to make sure I didn’t forget anything and he hopped in the plane as well. I diligently went through the pre engine start checklist:

Seats/seatbelts- on

Fuel selector- switch

Flaps- set 0

Circuit breakers- set in

Electrical switches- off

Mixture- full forward

Throttle- open 1/4th

Panel lights- as required

Checklist complete

Time to start the engine:

Battery master switch- on

Alternator- on

Fuel pump- on

Prime- 3 seconds

Prop area- cleared

Starter- engage

As the engine roared alive, I finished the first few checklists and got ready to taxi. I collected the weather, checked my brakes, and turned on all the lights. I radioed to the company’s frequency that I was outbound and made my way for the runway. After calling up ground control, I got a clearance to taxi to runway 32 via alpha, cross runway 1, to alpha run up area.

In the run-up area, I pulled the plane into the box, set the parking brake and went through the before takeoff checklist

Flight controls- free correct

Directional gyro- set to magnetic compass

Stabilator trim- neutral

Flaps- set 0

Windows/doors- locked

Seatbelt- on

Set throttle to 2000 rpm- set

Check magnetos- FAILED

As I was doing the before takeoff checklist, I went to check the magnetos. As I turned the key to the left magneto, I read a 150 rpm drop. Normal. I turned it back to both then to the right magneto. As I did so, the engine’s rpm started fluctuating uncontrollably. Magnetos are supposed to make the engine rpms drop no more than 175, but in this case, the rpms dropped well over 500 rpms. A problem. My instructor didn’t expect me to be able to fix the problem or know what to do so he helped me out. We idled in the run-up area and waited a few minutes to try it again. After trying it again, the same thing happened. The rpms dropped about 600 this time. My instructor called state ops and told them we were inbound in an aircraft with a faulty left magneto. My day was over.

A common airplane magneto. A magneto is a device inside the engine cowling which is responsible for starting the aircraft’s engine. The planes I use have two magnetos. This is for system redundancy, as well as for increased performance. With one magneto, the engine could get up to 2500 rpms, for example. However with 2, the rpms could go up to 2700 rpms. However, each one can produce 2500 rpms. So with 2, there’s added power, but not double power. A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce alternating current. This means that no power is needed to fire the magnetos because they operate on magnetism. So if there were to be an electrical failure in flight, the engine would still be able to run. The magnetos send an electric current to the spark plugs, in the cylinders, which ignite the fuel/air mixture which burns, turns the crankshaft, which turns the propeller. The turning propeller produces thrust and the plane moves through the air. So when I did the right magneto check earlier today, it dropped more than 175 rpms. This means that the right magneto wasn’t functioning properly and needed to be looked at.

A good lesson, but at the cost of a flight lesson. Luckily I didn’t get charged for the time I was in the airplane.

Every pilot license has certain criteria which need to be met for a student pilot to obtain it. The first license any pilot anywhere, no matter what, gets is the private pilot license, or PPL. Some of the requirements for the PPL are a minimum of 40 hours flight time, 10 hours solo time, and 3 hours BMI time. BMI time is also referred to as “under the hood” or instrument flying simulation. What they all mean is that while flying with an instructor the student puts on foggles. Foggles look like sunglasses but block the view of the outside world to the person wearing them. There is a cut out on the bottom of each lens so that the wearer can only see the control panel of the airplane and not look outside the windows. The purpose of this is to practice flying with no outside references, or flying in the clouds (instrument flying). So to get a PPL, aside from passing the flying and oral tests, the student also needs 3 hours under the hood time.

A pilot wearing Foggles Yesterday, my lesson was 90% under the hood. I took off and at 1500 feet, after doing the climb checklist; my instructor told me to put the foggles on. Once on, I flew the plane out to the practice grounds, over the ocean. When students wear the foggles, the instructor usually tells them what heading to turn and what altitude to stay at. Personally, I like flying with foggles on. Not because I can’t see outside, but because it make me a better pilot. For example, it’s easy to keep the wings level while you’re looking out to the horizon. Once the horizon changes its angle in relation to the dashboard of the plane, that means you’re turning the airplane. However, with no outside references, like the horizon, the student really needs to make sure he or she is watching the instrument panel closely. Flying under the hood really strengthens a student’s ability to scan the instruments. Having a good scan is paramount to being a good pilot.

Once in the practice grounds, my instructor had me do slow flight, and stall recoveries first. My slow flight was good. Unfortunately, when I do slow flight without foggles on, I watch the instruments a lot. This isn’t exactly what you’re supposed to do. I should be looking outside more than inside, but I developed a bad habit that I’m trying to break. Because of this habit, my slow flight under the hood was good. I did a climb, a turn, and a descending turn in slow flight. After that, the stalls were next. As I got the plane configured for a stall, I realized that the recovery was going to be harder without the outside references. My instructor must have been reading my mind because as I was thinking that, he told me that I need to just recover from the stall as I would if I wasn’t wearing foggles. The recovery is the same, except for the fact that I’ll be looking at the instruments and not the ground outside. As I stalled the plane in the power off configuration, I realized I was losing a lot of altitude. I quickly nosed up, but put the plane into a secondary stall. The secondary stall occurs when recovering from a stall; the nose is raised before sufficient air is flowing over the wings. I practiced this stall along with the power on stall multiple times before moving on.

Piper Warrior cockpit. What I was looking at all lesson After these maneuvers, my instructor had me track the Deer Park VOR. I’ve tracked VORs many times by now so this wasn’t too much of a big deal under the hood. I identified the station, selected VLOC on the GPS and turned the OBS to the station. Once my instructor saw me do this, he told me to break off from the 205 radial TO Deer Park VOR, and head back out over the Atlantic. Once there, I practiced unusual attitude recoveries. Without foggles, I really like these. In order to practice these maneuvers, the instructor changes the plane’s banks, pitch, and power while the student has his head down so he can’t see outside. So while wearing the foggles, I put my head down and enjoyed the change in G’s while he maneuvered the airplane. As he was doing this I thought to myself the recovery procedures. Pitch up bank: add power, lower nose, neutralize ailerons. Pitch down bank: power to idle, neutralize ailerons, nose up. I heard recover over the headset and simultaneously looked to the attitude indicator, grabbed the throttle with my right hand, and the control yoke with my left. I interpreted the instruments and determined I was nose high, banking right. I immediately added full throttle, lowered the nose, and rolled the plane back to the left. Perfect. It’s much harder to do these while having to look at instruments instead of the earth. The big difference is that while recovering from looking outside, the horizon is a large attitude indicator. Because of peripheral vision, I don’t need to be looking directly at the horizon to know what the plane is doing. However, while under the hood, I have look directly at the attitude indicator to know what the plane is doing. If I look at something else, like airspeed for example, I won’t still be able to see the artificial horizon. My instructor had me do several more recoveries then we headed back to the airport.

We only had time for 1 landing at this point, but it still needed to be good. The airport was using runway 19 and the winds were 24014G21 (14 knot winds out of 240 degrees [50 degrees off centerline] and gusting to 21 knots). Basically, strong winds from a large distance off the centerline. As I came in, I put in the crosswind correction, aileron into wind (so the plane doesn’t get blown off course) and opposite rudder (so the nose stays lined up with the centerline). I put the upwind wheel, right main gear, down first, and quickly lowered the nose and applied the brakes. A decent landing after a pretty good day of under the hood work

What I learned Today:

Simulating flying in IMC (instrument meteorological conditions) really helps all skills of piloting. Today my scan improved, and I gained confidence with keeping my heading and altitude. Something I wasn’t ready for, but handled well was unusual attitudes. Once I heard recover, my eyes started darting all over the panel to find out the information which would tell me how to recover. In all, simulated instrument flying is fun and good practice.

After last lesson’s simulated VOR navigation, I was ready for real navigation in the Warrior. Last lesson, I practiced tuning into VORs, identifying its’ signal and tracking to or from the VOR. I did well enough that my instructor said the next flight, today, would be a real VOR tracking flight. When I checked out the weather for the day, I didn’t think I was going to fly. Clouds were all over the sky, and they kept changing on the weather reports. When I was ready for the preflight brief, the clouds opened slightly up to 3000 feet so VFR fight was possible.

After filling paperwork, getting current weather, pre-flighting the plane, starting the engine, taxing to the active runway and taking off, my instructor told me to put on my foggles while I was only at 600 feet. Foggles is a tool which allows student pilots to practice flying a plane while in the clouds, known as instrument flying rules. They look like sunglasses but are blacked out. There is a small opening on the bottom of both lenses so that while looking forward I can only see the instrument panel and not outside.

My instructor wanted me to practice IFR, also referred to as under the hood, so I put the foggles on. At 600 feet, he started instructing me to the nearest VOR, Deer Park several miles away. I looked up the frequency, tuned to it and identified the Morse code.

A VOR instrument inside the cockpit

|

A VOR station on the ground

|

I made my way over to the Deer Park VOR and passed over it. Once the FROM indication popped up, my instructor told me to fly To the Bridgeport VOR. Bridgeport is an airport with a VOR located on the south shore of Connecticut. While I was doing this, my instructor got on the radio with New York Approach. NY approach is the approach pilots called up before going into McArthur Airport; a class C airport. This allowed NY approach to monitor us and tell us about other traffic in the area. Once I was on track to Bridgeport VOR, I was heading north. After about 3 minutes, my instructor took the controls. I didn’t know it because I was still wearing the foggles, but we had flown over some clouds. He told me to look where we were. I took off the set and looked outside. We were only 20 feet above a cloud layer and turning to go back to Long Island. Student pilots who do not have an Instrument Flight Rating aren’t allowed to fly over clouds. I didn’t do anything wrong; my instructor didn’t know the clouds were worse over the sound. Once turned around, I started tracking Calverton VOR. Again, I tuned into its’ frequency and identified it.

Once I flew over the VOR, I started tracking FROM the station. This took us out over the Ocean now. We had flown down Long Island, which took about 6 minutes, and were headed out to sea. Finally, after making it out to the ocean, I was going to practice some maneuvers. I took the foggles off for the VOR tracking of Calverton, but for a power off and power on stall, my instructor wanted me to put them back on. I got the plane ready for the stall. I stalled the plane and couldn’t remember a thing about stall recoveries. My mind went blank and I was confused from the foggles. My instructor didn’t want me to practice another power off stall, just a power on stall this time. This recovery went a little better, but still not very good. It was a lot harder to recover from a stall while under the hood than in VFR conditions. Without the outside references, maneuvers get a lot harder.

At this point we were over Captree Island and radioed Republic tower to come in for a landing. Since the weather wasn’t so good today, there was no one else in the pattern and it took us only a few minutes to taxi back to Echo ramp

What I learned today:

VOR tracking is very important for navigation. For example, today I would have gotten lost in the clouds if I was flying alone. However, if I did get lost, than I would still know where I was going because I was tracking the VOR. Also, being proficient in maneuvers as a private pilot will greatly help me once I start instrument flying. Everything gets harder when you can’t see outside.

Today was the first time I flew the simulator. The flight school has a large room with flight simulators in them for the students to use. There are pros and cons with using the sims. First off, using the sim as a lesson is much cheaper than a plane. There’s no fuel, and landing fees. Another pro is that there’s no danger, like when flying an airplane. However, the feel of using the sim is not even close to the feel of a real airplane. While piloting the sim, there is pressure on the yolk, like in a real plane, but it is infrequent and can’t be relied on to know what the plane wants to do. The instruments are extremely sensitive also, which makes it hard to stay on a specific heading and altitude for an extended period of time. What the simulator is good for is what I did today; practicing VOR navigation.

Computer image of what the simulator looks like.

VOR navigation is a way to know where you’re going, while flying. Simply put, VORs are stations on the ground, which emit a signal in all directions. The signal is picked up by the transponder in the airplane and displays data in the cockpit. Basically, the plane will track a signal from the VOR. Then the pilot can fly on a specified heading to or away from the VOR station, and know where he or she is.

I was using the largest and most expensive simulator today. There’s a real sized cockpit in the room with a 180 degree screen in front of it which displays a picture of what I would see if I was actually flying outside. All geographical landmarks, airports, VORs, and other navigation aids are 100% accurate in the simulator, compared to reality.

When the sim turned on, I was already lined up with the runway. Instructors don’t really care about taxiing and contacting tower while using the sim. I used the throttle to accelerate, and took off, trying to maintain what I would do in a real flight. (climb out at Vy, and keep a heading of the centerline) When I got to 2000 feet I leveled off as best as I could, and assessed my flight so far

First, my instructor told me how to use the GPS to find the nearest VORs to me. I found the closest one, deer park, and noted the frequency. With my instructor’s help, I put in the frequency, and listened to the Morse code. After confirming the Morse code signal, I turned the needle on the VOR instrument in the cockpit, until it was lined up with the center line. If the line moves left or right, that means I’m off course. From turning the CDI knob, I read a heading of 165. I flew this course and eventually intersected the course I needed to fly in order to get to the VOR. Unfortunately, I still need more practice using VORs. My instructor had to help me a lot while flying. I practiced tuning to 2 more VORs before trying to figure out the GPS

The GPS is much simpler to use, and contains more information. The GPS has many functions, but one of them is that a pilot can use it just like a VOR. The only difference is that the VOR is digitally displayed on the GPS interface instead of on an analogue dial. Another function of the GPS is that it can tune into more than just VOR signals, or stations. There is a database pre-programmed into the GPS system that has a lot of waypoints that the GPS can also tune into. The advantage of this is that the GPS isn’t limited to what it can identify. Instead of tuning into a VOR’s signal, we tuned into Republic airport’s signal. The GPS automatically identified the station and displayed a direct route to the field. Because I was in a simulator, airspace was no factor. (no factor is a term used in aviation which means it doesn’t matter. For example, often while on final approach over 3 miles out, the tower will tell me that another plane is going to be taking off before I land. After the airplane on the ground takes off, the tower will radio to me and say that the traffic is no factor; meaning the taking off airplane doesn’t pose a problem to my landing)I made an ok landing, not bad for a simulation, and turned the machine off. Hopefully next lesson, in two days, I’ll be able to fly a real airplane and practice VOR navigation.

SOLO! Third one, finally. My last solo was over two months ago because I ran out of money last semester, and because the weather hasn’t cooperated this semester. Before going to the flight center around noon, 1700 zulu, I was unsure about the weather; the clouds were starting to roll in for an afternoon snow storm. The morning was sunny and cold, perfect for flying. Winds were coming out of 320, right down the runway, at only 4 knots. I was thinking that if the clouds hold off for a little bit, I’d be able to solo for my third time.

I got to the flight center and checked the weather. Winds 32004; visibility 10SM, ceiling OVC050 (5,000 ft); and an altimeter setting of 30.12. I met with my instructor and he told me it was good for a solo. He told me I needed to be up there for at least 1.6 hours. This is because I already had 2.5 hours solo so far, and need at least 10 solo hours to get my private pilot license. With the 3, 2 hour each, solo cross countries in stage 3 of the course, a minimum of 1.5 today would ensure I would reach 10 solo hours.

I did the preflight paperwork, and realized that without my instructor in the plane with me, the takeoff and landing distances were much shorter than I’m use to. This wasn’t a problem, in fact, I prefered it. Once he signed my logbook and student pilot certificate, I went out to the plane and did the preflight inspection. During the walk around, I found a missing nut and washer inside the air intake, on the engine cowling. I was hoping it wouldn’t stop me from my flight, but I told the air boss anyway. He had a mechanic come out within minutes to fix it. I checked his work (after all, I would be flying the plane alone. I wanted to make sure the plane was perfect). The oil was fine, fuel was just put in both wing tanks, and the brake fluid was at the correct level. I hopped in and started the engine. Once I was ready to taxi, I cleared myself with the Airboss, “State 66 outbound” and taxied to the edge of the ramp.

The taxiing went alright and I got to the run-up area without any problems. Every time I looked to my right at the empty seat, I felt a little rush of adrenalin. At the run-up area, I checked the magnetos (the magnetic batteries which are responsible for turning the engine crankshaft), set the flaps to 0, and prepared the plane for takeoff. I taxied out of the run-up area, and stopped at the runway threshold hold line. As I turned to tower frequency, I was already being called from the tower. They saw that I was number one on Bravo side (the name of the taxiway) for runway 32. I responded “Farmingdale State 66 number 1 on Bravo for runway 32.” The tower told me to line-up and wait. I increased rpms to taxi speed and lined up with the runway centerline (line up and wait means that I line up with the runway’s centerline and wait for a takeoff clearance). As I was lining up, I got the clearance to takeoff.

The plane started rolling and got to rotation speed. I slightly pulled the controls back and the wheels left the ground. Since I do most of my training between 2000 and 3000 feet, I wanted to climb to 5000 feet. So I climbed out and did the climb checklist. I was headed for a VFR waypoint, Captree Island. I looked at my frequencies to make sure they were correct, and when I looked up, I couldn’t see anything. I looked all around, out every window but everything turned white. I had flown into the clouds by accident. The clouds had lowered from 5000 ft to about 2900 feet. I immediately took the power out to descent power and pitched the nose down 3 degrees. I was probably at 3100 feet when everything went white, so I didn’t have far to descent. After 50 feet, Captree Island started to come into view, out of the white haze. I decided to stay at 2500 feet until I got to the practice ground.

This was the first time I was out of the airport traffic pattern by myself. I knew right away that if anything goes wrong, it was me only me who could solve the problem. This thought got my heart racing a little more, but also made me smile. I was out over the Atlantic Ocean, in an airplane by myself, and I was the only one flying the plane! It made me feel amazing at what I have had accomplished so far, but also made me realize that I had a lot of work still to do.

In the practice area, I did some slow flight, and stall recoveries. My instructor told me to do whatever I wanted, since there wouldn’t really be anyone to tell me what to do. I also made my way down the southern coast of Long Island. I made it to east Hampton, and could even see Montauk point. By the time I got out there, I only had enough time to get back home. I was aiming for 1.5 hours, so I knew I could get at least that.

After the 10 minute flight back to Captree Island, I got the weather report and was ready to call tower for a landing.

“Farmingdale State 66 is at Captree with Charlie, requesting touch and goes”

-nothing

“Farmingdale State 66 is at Captree with Charlie, requesting touch and goes”

-nothing

Again: “Farmingdale State 66 is at Captree with Charlie, requesting touch and goes”

-again nothing

I thought right away, not again. My last solo, almost 2 months ago, I had problems with the communications. I circled back out over the ocean because I was getting too close to Republic’s airspace. Again I called out “Farmingdale State 66 is at Captree with Charlie, requesting touch and goes” but again nothing. Great, a communication failure while I was in flight, alone. I was trying to think of the transponder code for a communication failure, when I remembered what I did last time. I switched my headset to comms 2, the communications the co-pilot uses. This time I said, with a little urgency in my voice,

“Republic tower, Farmingdale state 66, inbound for a landing”

“Republic tower, State 66 report to final”

Finally, after 8 minutes of thinking I had a real problem, I was in communication with the tower. From then on, I had to press the button on comms 2 instead of 1, but I had avoided a situation on a solo.

The approach and landing went fine, and I taxied to Echo ramp to tie the plane down. I met with my instructor and we went over my flight. As I walked out to my car, my heart started to slow down to a normal beat and I thought how much fun I just had.

What I Learned:

Not every bad situation is an emergency. Often times, there is a simple solution to a problem that people overlook. Being a pilot is 50% flying airplanes and 50% overcoming situations. Today gave me a huge boost of confidence in both areas of piloting.

|